Why We Should Train Like Athletes: The Mental Hacks You Are Missing

Introduction

We have all been there. You practiced that one difficult run until your fingers ached. You know the music cold. Yet the second you step onto the stage, your heart starts pounding. Your palms get sweaty. Suddenly, your brain feels like it is buffering.

Why does this happen? More importantly, why do elite athletes seem to handle it better? They face screaming stadiums and high stakes, yet they often perform with incredible consistency.

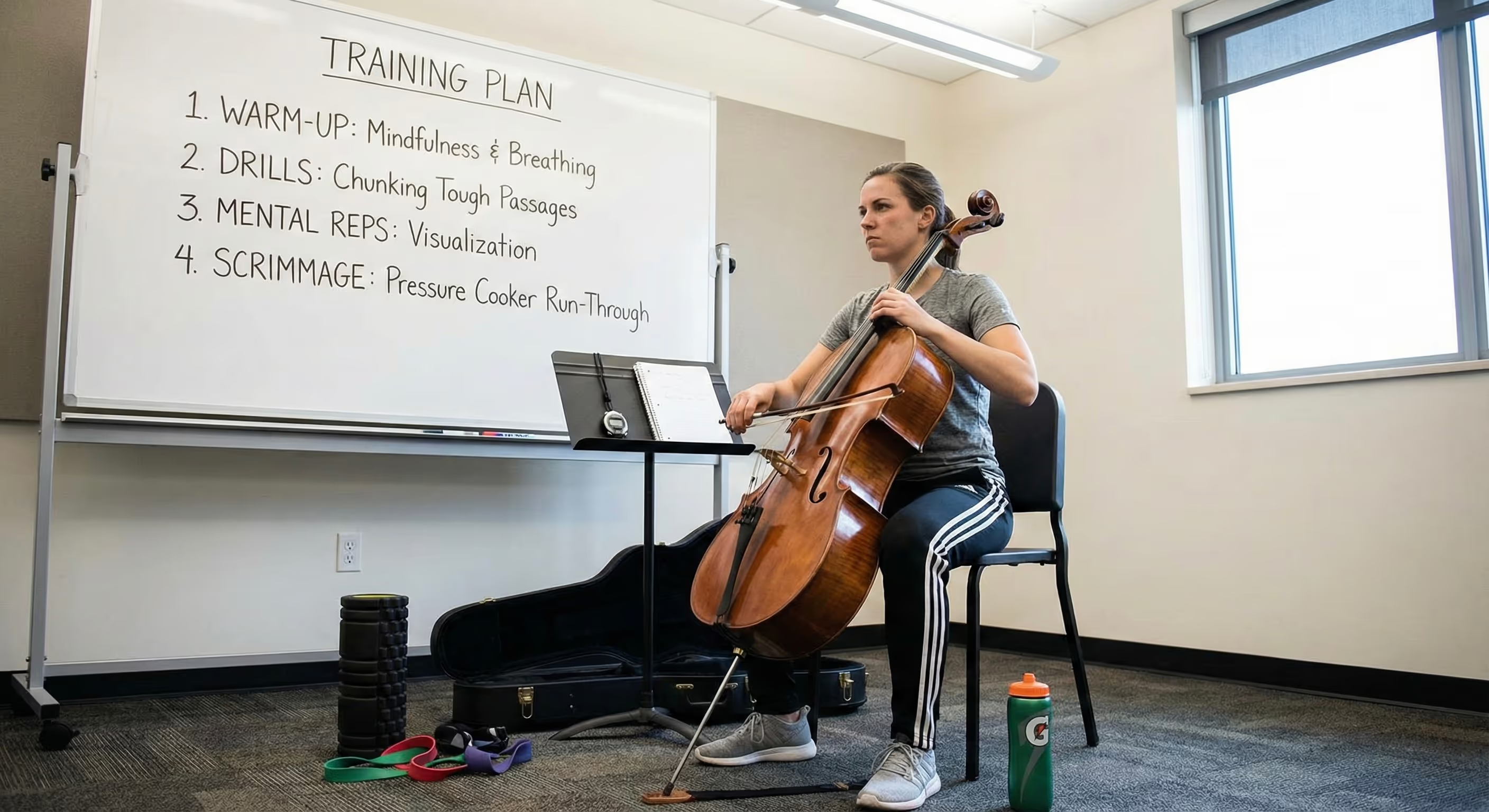

I recently took a deep dive into this exact problem for a literature review I published in the IJSRET. I wanted to explore how we can adapt pre-performance protocols from sports psychology for music education. My research suggests that we have been missing a huge piece of the puzzle. While music education focuses heavily on technique and interpretation, it often ignores the mental game. Meanwhile, sports psychology has spent decades perfecting routines to help athletes win championships.

Here is what I found in my research and how you can use these athletic secrets to hack your brain and level up your musical performance.

Why athletes don’t “wing it” (and musicians often do)

Sports psychology has a long track record of treating the minutes before performance like part of training, not dead time. The point isn’t superstition. It’s functional:

- Manage arousal (not too sleepy, not too panicked)

- Focus attention

- Create consistency so your body knows “we’ve done this before”

Your review highlights a gap: music training usually goes hard on technique and interpretation, but often stays weirdly informal about the psychological warm-up, even though musicians face the same pressure to execute repeatedly under stress.

That gap matters because when you don’t have a plan, your brain fills the silence with chaos. In your paper’s framing, lack of formal preparation can expose musicians to uncertainty and anxiety.

Why musicians freeze under pressure?

When the stakes rise, your attention changes. Instead of hearing the phrase, you start monitoring your fingers. Instead of communicating musical shape, you start checking for mistakes. Your brain zooms in on micro-control, and that often makes things worse because skilled performance relies on automatic coordination.

Another issue is uncertainty. If you do not know what to do right before you perform, your mind will fill the space. People replay worst-case outcomes, compare themselves to others, or obsess over one spot that went wrong yesterday. None of that helps you play.

A routine solves this with one simple principle: reduce decision-making. When you always do the same steps, you do not waste energy wondering what to do. You just do it.

Playing a piece from start to finish over and over is inefficient. Instead, you should break difficult tasks into tiny and manageable chunks. For a musician, this means isolating a specific phrase or technical hurdle. For an athlete, it might mean practicing a specific swing. This method helps you master the components before putting the whole puzzle together. Researchers Miksza and Tan found that this approach leads to much better consistency.

But here is the wild part. You can practice without even touching your instrument. This is called mental imagery or visualization.

Athletes do this constantly. They close their eyes and visualize the perfect shot. My research confirms that mental practice works for us too. A violinist might close their eyes and imagine the weight of the bow, the sound of the tone, and the shift of their left hand. It is a way to get reps in without physically wearing yourself out. Studies show it improves performance quality just as well as it does in sports.

Five athlete tools that transfer insanely well to music

1. Mindfulness, aka attention training

Mindfulness is not a personality trait. It is practice for your attention. You train the skill of noticing where your mind went, then bringing it back.

For performance, this matters because your mind will wander. The question is whether you can redirect quickly without spiraling. Even a short daily practice can make it easier to stay present on stage.

Think of it like closing background apps before running a heavy game. Your phone is the same phone, but it runs smoother.

------------

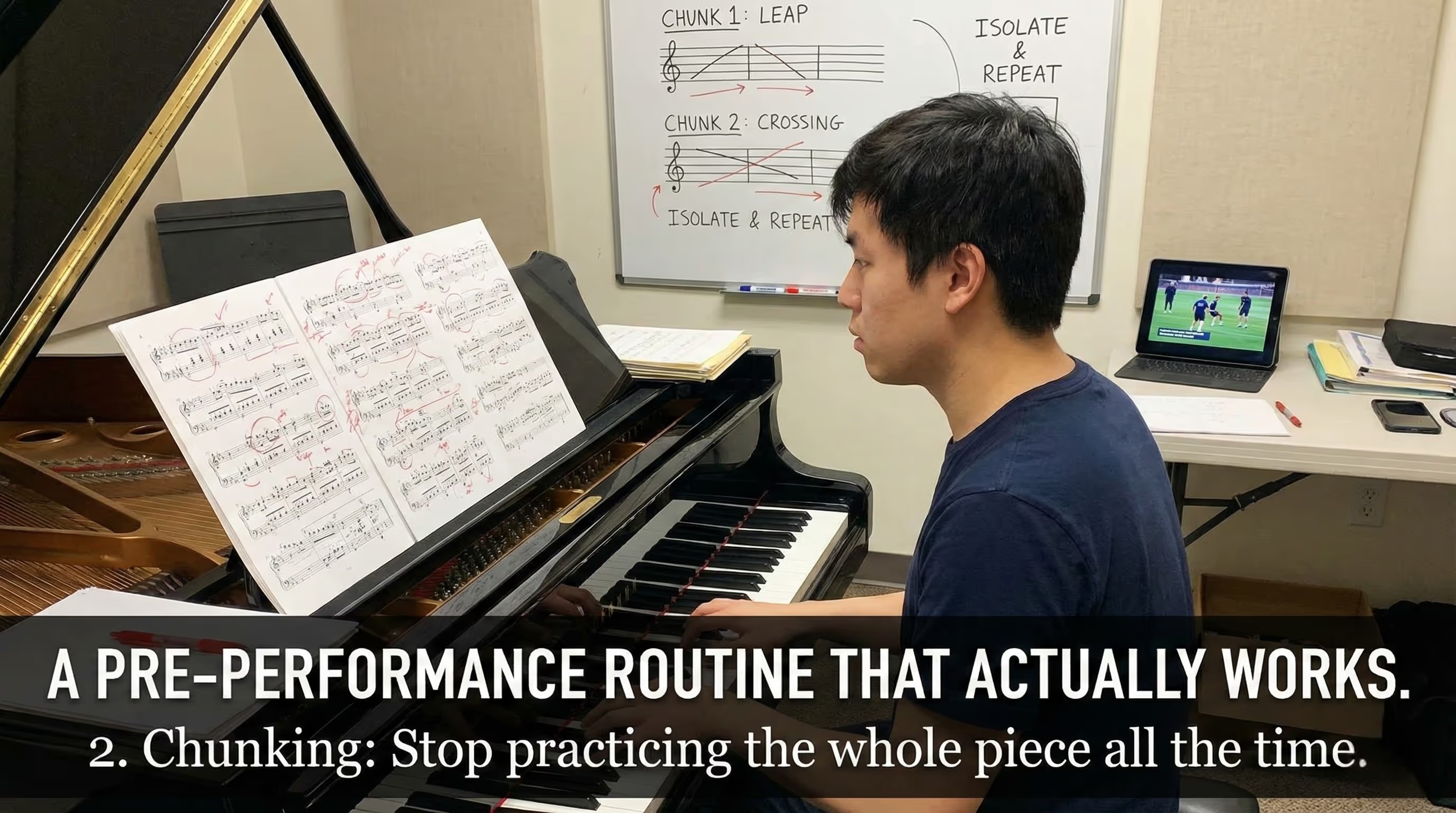

2. Chunking, aka stop practicing the whole piece all the time

Musicians often practice like this: play from the top, mess up, restart, repeat.

Athletes do not learn complex skills that way. They isolate components, repeat them until stable, then recombine.

Chunking means breaking music into small performance units. Not just measures, but events: the leap into the chord, the voicing shift, the hand crossing, the entrance after a rest. You master each unit, then connect them.

If your practice feels messy, your chunks are probably too big.

------------

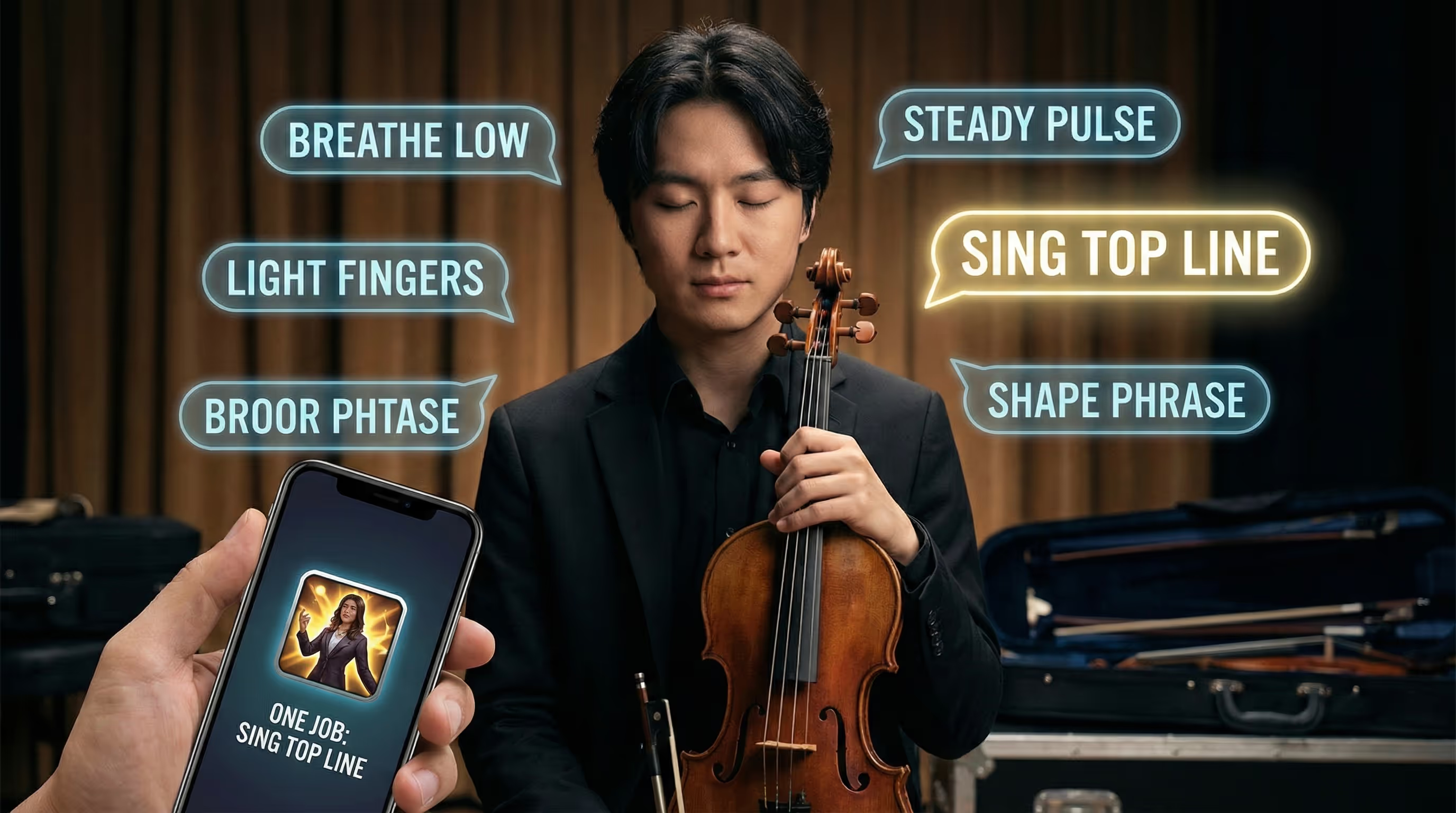

3. Cue words and self-talk, aka one job at a time

Under stress, the brain cannot hold ten instructions. If you try to control everything, you control nothing.

Cue words are short triggers that guide your attention. Examples:

- steady pulse

- light fingers

- sing the top line

- breathe low

- shape the phrase

Pick one or two. That is it.

This is like a character ability in a game: one command that changes your behavior. Not a paragraph.

------------

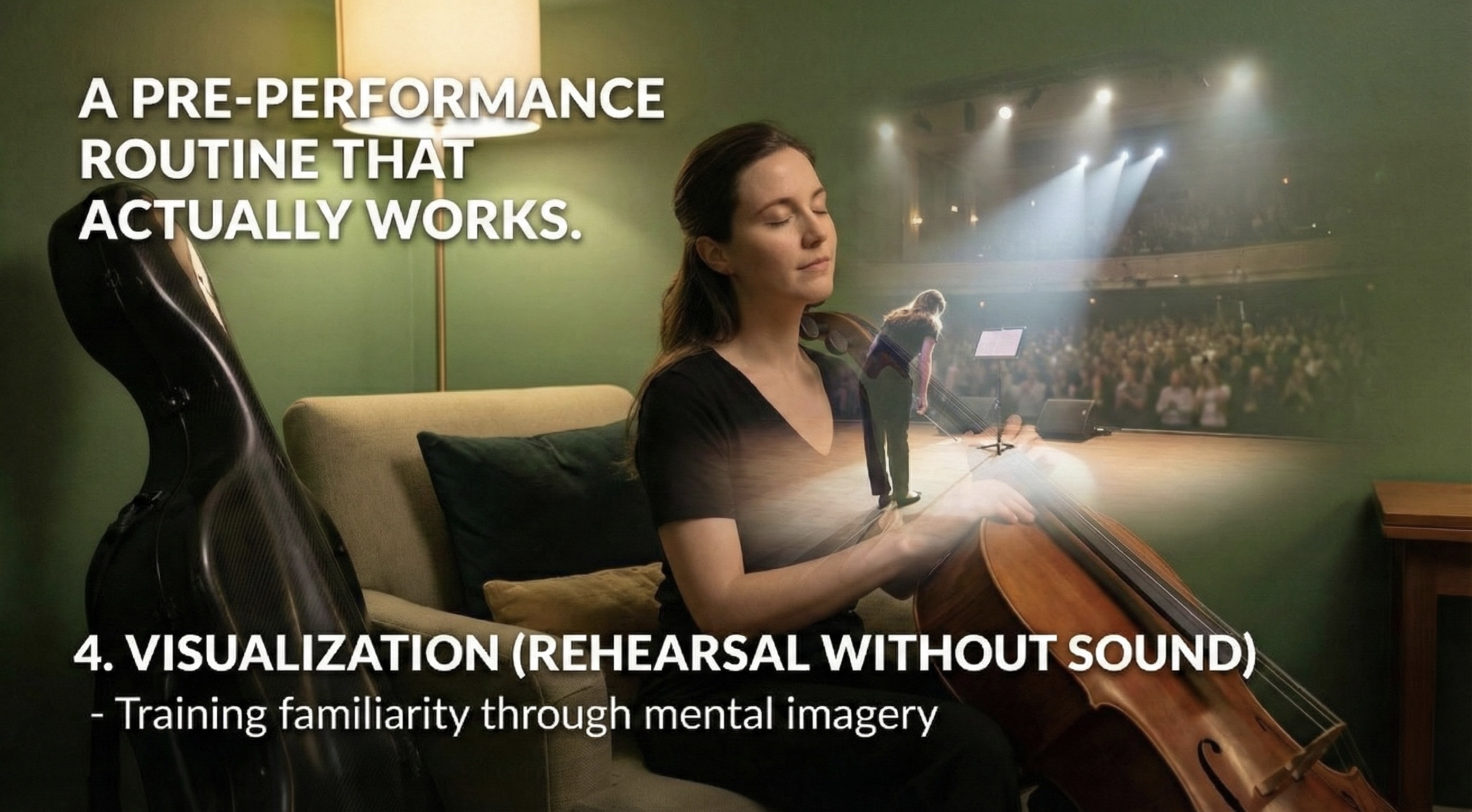

4. Visualization, aka rehearsal without sound

Mental imagery is performance practice without the instrument. You picture walking on stage, the first sound, the tempo, the feel of the keys or bow, the hall, the lighting, the body sensations.

This helps because the brain responds to imagined scenarios similarly to real ones. You are training familiarity. When you later do the real thing, it feels less like a first time and more like a repeat.

Do not aim for perfect imagery. Aim for stable imagery.

------------

5. Pressure training, aka stop saving stress for the big day

If the only time you experience pressure is on stage, your brain will treat performance as a threat.

Athletes build pressure gradually. Musicians should too. You create layers of exposure:

- play for a friend

- record one take only

- simulate recital conditions

- do run-throughs with no stopping

- perform mini-concerts weekly

Pressure becomes a normal part of your process, not an emergency.

A simple 10-minute pre-performance routine

you can steal

This is a template. Customize it, but keep it consistent. Consistency is the entire point.

Minute 0 to 2: Reset the body

- Slow breathing, longer exhale than inhale

- Release jaw, shoulders, hands

- Feel both feet on the ground

Minute 2 to 4: Choose your focus cue

- Pick one or two cue words

- Repeat them calmly

- If negative thoughts show up, do not argue with them, just return to the cue

Minute 4 to 6: Mental movie

- Visualize walking on stage

- Visualize the first 20 to 30 seconds

- Hear the sound you want, feel the timing, picture the physical motion

Minute 6 to 9: Micro-warm up with

attention switching

- Play a tiny anchor section

- Switch attention intentionally

- melody only

- rhythm and pulse only

- sound quality only

- Keep it short and controlled

Minute 9 to 10: One commitment

Decide what success means today in one sentence. Examples:

- I keep the pulse and tell the story

- I stay present and recover quickly

- I commit to sound and shape

This prevents perfectionism from hijacking your brain.

The Physiological Reset: Just Breathe

One effective technique backed by research is rhythmic breathing. My paper discusses the effectiveness of breathing exercises in reducing anxiety for conservatory students. A common method is the 4 7 8 pattern where you inhale for 4 counts, hold for 7 counts, and exhale for 8 counts. It forces your nervous system to calm down. Integrating breathing exercises into your lessons can dramatically reduce physical symptoms of anxiety.

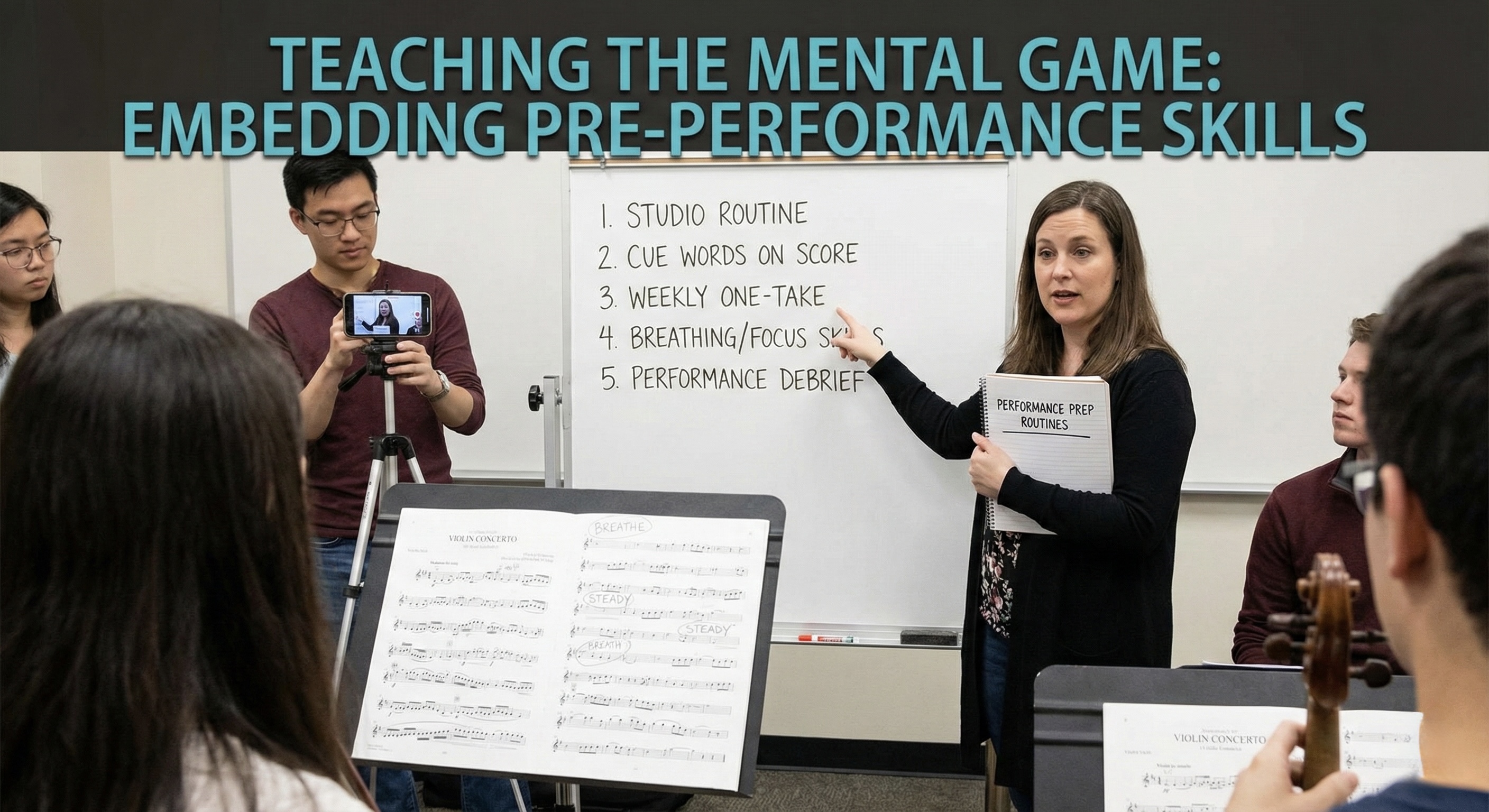

What teachers should start doing immediately

If you teach, the most honest critique is this: music education often treats mental preparation as optional, or only for anxious students.

That is backwards.

Pre-performance skills should be standard, like scales. Every student benefits from learning how to focus, regulate arousal, and handle pressure. Even students who seem fearless can build more consistency and healthier performance habits.

Practical ways to embed this:

- Make a routine part of studio class

- Ask students to write their cue words on the score

- Require one-take recordings weekly

- Teach breathing and focus as normal skills, not therapy

- Debrief performances the way athletes do: what worked, what did not, what changes next time

Reality check: this is not one-size-fits-all

Not every method works equally for every person, genre, or level. A conservatory violinist and a beginner singer do not need the same routine. A jazz gig has different demands than a competition.

Also, a lot of research leans heavily toward Western classical contexts and advanced performers. That means we should be careful about pretending the evidence covers everyone perfectly.

Still, the main idea is very solid: structured preparation improves consistency and gives musicians practical tools to manage stress rather than being controlled by it.

The Bottom Line: We Need a New Approach:

The findings from my review are clear. The old school way of music education is often reactive. It waits for problems like stage fright to appear before trying to fix them.

Sports psychology offers a proactive model. By stealing these protocols like mindfulness, chunking, visualization, and pressure training, we can build a psychological toolkit. These tools make us resilient, flexible, and ready for anything.

Musicians love talking about artistry, inspiration, and magic. But the truth is brutal: on stage, your body runs the show. If your nervous system is chaotic, artistry becomes harder to access.

A pre-performance routine is how you make artistry more available under pressure. It is not about becoming emotionless. It is about building a repeatable doorway into your best state.

So the next time you head to the practice room, think like an athlete. Do not just train your fingers. Train your brain. The difference between a good performance and a legendary one is not just in the notes. It is in the mind. Do not rely on hope right before you play. Build a protocol. Athletes already proved it works.

More from DHub

Explore more stories and insights from us.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.